In Sweden there is an everyman’s right (Allemansrätten) to roam freely through the landscape, even if in private ownership. This gave us an opportunity for an old-style sailing expedition with my fireåring Skíðblaðnir, a traditional clinker-built boat from Denmark similar to a Norwegian oselver. The challenge: We neither had electronic aids nor an engine. Only a GPS data logger was switched on but never used to determine a position. The vessel was propulsed by sails or oars only. The only “modern” concession was the use of a nautical chart as the only navigational aid. We followed a leg of a 13th-century route description, colloquially known as ‘King Valdemar’s itinerary‘.

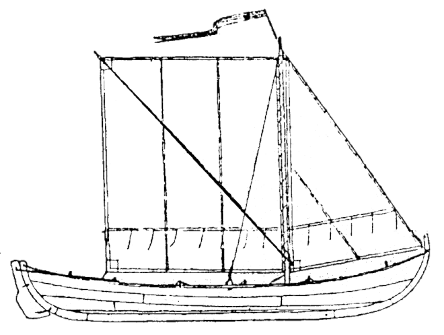

Name: Skíðblaðnir

Type: Fireåring (reconstruction)

Rig: sprit-rigged

Built 1997 by the Maritimt Forsøgscenter, Lyndby (Denmark)

Length: 7.1 metres

Beam: 1.7 metres

Draught: 0.4 metres

Sail area: 11.5 m²

In my ownership: 2006-2015

Monday: On Monday I picked up my crew in Stockholm; my younger brother Tobias and Alexis – an old friend from university – and looked for a good location to launch the boat. We decided to launch in Nynäshamn, which was located at the inner route of Valdemar’s itinerary. Before launching, we supplemented our equipment and stopped at the Havn bakery – a place that we frequented from then as often as possible.

Shortly after the boat was in the water, it filled up quickly with water. Suspecting that the vibration of the transport has opened an old crack, I searched for the leak, armed with a container of bitumen, which has the advantage to be also applied on wet surfaces (as opposed to pitch). In the meanwhile my crew ripped out the floor-boards and bailed out in great haste. Finally the leak was detected. It was not really a leak at all, but a hole which I should have been very well aware of and through which water spouted in almost like a fountain. It is always kept open when the boat is on the trailer, to allow the discharge of rain-water. Well, this first test was of course “intended” and I was very content to see the quick-witted reaction of my crew in the first distress situation, standing there with wet feet, but not murmuring but doing what was necessary to prevent the vessel from sinking. It was already late in the afternoon, so we deferred the departure to the next day, since the remaining time of daylight would not have allowed us to find a suitable mooring place for setting up a camp. Moreover, it started to rain, which would have dampened the enthusiasm even more, so we decided to remain one more day in civilization.

Tuesday: After a breakfast at the Havn bakery, the boat was bailed out again. At that point we thought it was only rain-water. Then we finally started. We rowed out from the harbour and set sails with wind from abaft in a southerly direction. With a modest draught of about 40 cm it was possible to sail in most areas, yet we nearly ran aground at the very start. The archipelago is full of treacherous shallows and reefs, emphasizing the importance of an alert look-out. We sailed swiftly in between rocky reefs, while Tobias called out where the reefs were. Not an easy task, since most shallows and reefs are detectable if viewed from a steep angle, as the remaining water is hazed by the reflection of the sky. We sailed through a narrow passage between the mainland and the island of Järflotta and entered more sheltered waters. We rowed through the Draget Canal, which was a very interesting site indeed, as this “chocking point” must have been traversed by ships following the itinerary 800 years ago, being located directly between Svärdsund and Ekholmen. The canal in its current form is a mid 19th-century structure. Albeit there might have been previous canals, it seems very likely that there was none before the invention of dynamite. Although the coastline in this region would have been some 2.8 metres above the current level 800 years ago, due to post-glacial rebound, the height of the steep canal’s sides cast doubt that this isthmus would have been completely inundated at that time. In a recent article I formulated the hypothesis that this was a portage back then, as indicated by the very toponym itself, i.e. “drag” literally to pull, and “et” – or the more commonly used “eid” – as isthmus. These toponyms are very often found combined in the Scandinavian world. After an hour of sailing we returned through the same canal, hauled down the sail and rowed to Ekholmen on Järflotta, which is also mentioned in the itinerary, where we set up our first camp. We were stunned by the tranquility of the scene and felt privileged to reconnect to nature. After having moored the vessel – with iron bolts hammered into the crevices of the rocks – and brought most of our equipment on land, we started to collect firewood and built up the tent.

We cooked a stew and regretted not to have brought wine and meat. Yet herbs and spices made it a hearty meal, which was all the more enjoyable after the day’s labour. If the night was not so infested by mosquitoes, it would have been perfect.

Wednesday: The next day we were not in a hurry to leave our mooring, but cooked a morning coffee. It was refined by pieces of ash flying into the kettle from the crackling fire. After our spirits were revived by this, we slowly packed up and continued the voyage in the late morning. We were traveling north to follow King Valdemar’s itinerary to Yxlösund. We passed by Nynäshamn again, a place that did not exist in the Middle Ages, but nevertheless we thought there is no harm in making a refueling stop. We noticed that one of the water bags has not been closed properly and needed to top up our water provisions. Of course, at this opportunity we paid our favourite bakery a visit as well. After some idle time, we continued further north. There was only a slack breeze and we had to be wary not to cross the fairway of the Gotland ferry. The sky was veiled in grey mist while we were beating against the wind, but gained not much height. The industrial estates of Nynäshamn kept depressingly long in sight. While the weather was anything else than welcoming, we kept the spirit up by singing shanties (if only we had learned some texts…refrains were the only bits we could remember). In the distance we sighted the entrance to Yxlösund and longed for the moment to set up the tent to find some rest at a warming fire. The last bit was rowed as the wind slackened. While the bridge over the sound was visible, we decided to sail into a small harbour in the next bay, because there were some traces of civilisation. Since it was already too late to prepare a dinner, we hoped to find an inn in this harbour. Our vision was very much deceived, because from the entrance one gained the impression that we could row up into the harbour within only 10 minutes. We rowed and rowed and the harbour did not seem to come closer. Since it was a very long-stretched bay, it took four times as long. When we arrived, the harbour made a very desolate impression; we haven’t met a soul, only in the distance were some summer houses with warm orange light emanating from the windows. There was a ship scrapping site, and only few yachts were moored at the jetty, which was obliterated by old nets and fenders, rusty nails and wooden planks. By now the rain has increased, and so had our desire to find a warm and dry spot. I sent my crew out to scout out a suitable place to (A) put up the tent and (B) to find us an inn, for the well-deserved hearty meal we had already so vividly before our eyes, while I started to bail out the boat and made sure that our equipment remains reasonably dry. Both Alex and Tobi came back with bad news. Our crew was put to the first test, as the mood has reached a low mark and we could not agree on what to do with ourselves, simply for the lack of good options. Finally I came up with the idea to rig up the tent on the boat, pulling the top up with a halyard, while fastening the lower ends to the gunwale. While my plan was viewed with scepticism at first, it was later admitted that it actually worked quite well. Although this did not allow us to sleep on the boat, it would have kept us reasonably dry. But Tobi had scouted out a shelter on a construction site, so my crew decided to abandon the ship and to roll out their sleeping bags there, while I was too stubborn as not to “reap the harvest” of my fine invention. It was necessary to stay nearby the boat in any case, because it needed to be bailed out regularly, since we noticed that there must be still a leak somewhere. So I put my sea bag on a thwart and clung on it, while shivering in my damp clothes. During the night I woke up almost every 2 hours to bail out the boat, apparently the “internal alarm clock” works very reliable when waking up is of crucial importance for not ending up in a bath tub. Yes, in such situations one has to ask why one puts oneself into such situations. Well, the next day made up for it entirely.

Thursday: This time I was not woken by the anguish to drown, but by gently warming sun beams. Never did I appreciate the sun as much as in this moment. So the first thing we did was to lay out all our equipment (and finally ourselves) to dry. If we had a schedule on this day, we could not care less. Our first meal was an early lunch, a warm soup cooked with the paraffin cooker. But this was not entirely a time for slackers, for I was determined to put the nightmare of a constantly leaking boat to an end and to find the leak. And there it was, beneath the floor boards in the stern, with water coming visibly in. I smeared bitumen into the leak, but the pressure of the water would find a way to extrude it. I tried to make a make-shift repair with an old hemp strand, hammering it into the bitumen. I was not surprised to be disappointed again, because the proper way would be to soak the strand in tar or hot pitch. But in the end the boat was dry, while my fingers were besmirched with bitumen. Finally we set sail. We were happy to leave the harbour of desolation and sailed with half-wind out of the bay. Initially my plan was to sail to Älvsnabben, a renowned anchorage of the outer route, and after that to Utö of the eastern route, where iron ore had been mined in the Middle Ages and which therefore might have played an important role in the context of the itinerary. But we had strong contrary winds from the north-east and our woolen sail was too slack, thus preventing us to beat effectively against the wind. So we sailed back south again. Under authentic circumstances, we would have waited for better wind, but with only few days in Sweden, we wanted to sail as often as possible. With 4 gales from abaft we made some speed. This time we withstood the temptation of Nynäshamn’s Havn bakery and free internet and sailed right through the strait.

We passed some houses on the shore and a man shouted something in Swedish and made an inviting gesture. Evidently thrilled to see a boat not propulsed by a motor and not built of glass-fibre, it seemed that he wanted to invite us. But we were determined to travel down with the gentle breeze. We arrived at a small island near Ekholmen and moored the vessel. The island was very nice, it was forested and had a sandy beach. We set up our camp again, made a fire and cooked a soup. The sky assumed a crimson colour and we exchanged some horror stories at the crackling fire. It was a very pleasant evening. But the sky clouded over and it started to rain again, so we retreated into the tent.

Friday: On the next morning our sleeping bags were soaked by the rain, which has lasted throughout the night. Tobi has left the tent much earlier and left a note, affixed to a twig, that he found shelter under a ledge, with an abbreviated description where it was located. We gathered there and had chocolate and biscuits for breakfast and read our books. Not entirely disconnected with civilization, we received the weather forecast, according to which it was not getting better in the next two days. Also the gale force increased from northerly direction. If there was a chance to get back to Nynäshamn in time, it was now. Therefore we decided to abbreviate the expedition, as not to risk to miss Alex’s and Tobi’s flights. We had already a gale of about 5 bft and the wind was constantly increasing, so we quickly packed up and laid the mast as to minimize the resistance, for there was no chance to beat against this wind with our slack sails. We rowed without a break through the swell, against wind and waves, and covered a distance of about 3 nautical miles. As we sensed that this was probably our last chance to get back in time, we put all our back in it. We constantly rotated the rowers and the helmsman, so that everyone could have a rest at the tiller. During the crossing we only spoke of food that was awaiting us in Nynäshamn, which we finally reached with great relief.

Saturday: To our dismay we realized on the next day that the weather forecast was wrong and that we suddenly had southerly winds, with which we could have easily traveled home. So the exertion of the previous day was in vain, yet we felt proud to have done it and regretted not a moment of it. On this day we took the ferry to Üto – like ordinary tourists – to see the medieval mines, where we initially wanted to call under sails. Still under the impression of the exertions and small adventures of the last days, we still felt a bit alien in modern civilization.