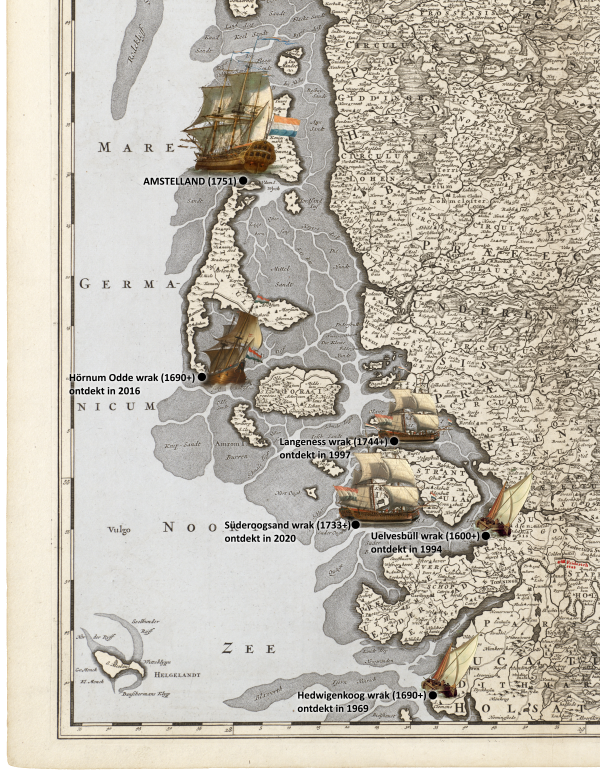

In the years 2016 – 2020, three hitherto unknown shipwrecks from the 17th-18th century were exposed by coastal erosion in the northern German federal state of Schleswig-Holstein. Although none of the new wrecks have been identified yet, two of the wrecks are of presumed Dutch origin, inferred from constructional particularities and other circumstantial evidence. Generally, the over-representation of Dutch wrecks in the North Frisian Wadden Sea is not surprising, as this region was historically closely linked to the Netherlands. In this short report, the author provides some interim research results from first-hand, which he is carrying out on behalf of the State Archaeology Department of Schleswig-Holstein. The research results are also updated in the MASS-database on the maritime cultural heritage, to which the author directly contributes on behalf of the Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed.

With the Wadden Sea, Schleswig-Holstein shares a special type of an intertidal landscape with the Netherlands and Denmark, which islands and coasts were colonised by the Frisians in the early Middle Ages. They were adapted to the bleak and hostile environment and lived under the permanent threat of storm-floods. The people were shaped by the sea, and most made their livelihood from the sea. Although politically never united, the cultural affinity of the North Frisians in Schleswig-Holstein to West Frisians in the Netherlands is well reflected by shipwrecks and other expressions of a genuine maritime culture.

Two new Dutch wrecks with double-planking

In October 2016, a new wreck became unearthed through coastal erosion at the southern tip of the island of Sylt – called Hörnum Odde. Although the wreck could ultimately not be saved due to coastal erosion and winter storms, some very significant details could be observed before its destruction, which suggest a Dutch origin. The slender frames were not interconnected, but only fastened to the planking. The planks on the other hand were massive in dimensions, and featured little wooden plugs known as spijkerpennen, which is a diagnostic feature for Dutch shell-first shipbuilding, which prevailed mainly in the 17th century and was described in Nicolaes Witsen’s 1671 published Aeoude en Hedendaegsche Scheepsbouw en bestier. Moreover, the hull features a double-layered oak planking, colloquially often referred to as “Double Dutch”, a feature that has been mainly associated with ships of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) since 1602, present inter alia in early 17th century wrecks like the BATAVIA, AVONSTER and MAURITIUS. These ships received a double-planking of oak with an additional third layer of pine to protect the hulls from marine borers in the warm tropical waters of the Indian Ocean, and thereby reduce shipyard maintenance in the colonies. With a date of ca. 1690, however, the Hörnum Odde wreck could not be associated with the only recorded VOC-ship that has foundered off Sylt’s coast, i.e. the AMSTELLAND, lost in 1751.

Local chronicles mention a Dutch ship of the West-Indische Compagnie (WIC), which ran aground with a valuable cargo of manufactured goods in a storm on 13th December 1703 near Hörnum, after having lost the rudder. According to the account, the entire crew of 29 drowned in an attempt to disembark, as their boat capsized in the great waves. Allegedly only its captain Jan Jacobs reached the land by clasping a plank. The local population well versed in beachcombing, salvaged the cargo. The salvage operation was shady, as the ship’s owner had difficulty to reclaim a part of his cargo. It seemed that even the shore-bailiff (Strandvogt) had his share in the illegal activities, as he was later dismissed.

Given the Dutch-style construction, the date, and the size of the shipwreck, it would not be wrong to hypothetically associate this wreck with this WIC-ship. The double-planking would have equally made sense in the Caribbean for the same reason as in the Dutch East Indies, and the shipwreck features tool-marks, which show that it was scrapped by the islanders.

Shortly after this author presented the Hörnum Odde wreck at an international shipwreck conference as the „youngest“ known Double Dutch construction, a second wreck of exactly the same constructional particularities – but even younger – was discovered in a tidal creek east of Süderoogsand in early 2020. The oak samples were dendrochronologically dated by Dr. Aoife Daly to around/after 1733. A fragment of a blue-glazed Delft fayence and a clay pipe were discovered in close proximity to the wreck. This is an extraordinary late date, as both the Dutch shell-first construction method and „Double Dutch“ have been associated with the 16th and 17th century, but not the 18th century. And what are the chances of finding two such „Double Dutch“ constructions within such a short time span and in such close proximity? This feature has been typically regarded as a rare and fleeting phenomon of the early 17th century, but it seems it was neither short-lived, nor rare. In fact, there are indications for double-planked vessels also from an undated keel from St. Peter-Ording and from a wreck near Langeness. The latter dates around 1744 and it has a first layer of oak planking and a second layer of pine planking. Tin spoons with the Amsterdam coat-of-arms and Dutch coins were scattered in the surrounding area. Although not all double-planked wrecks have to be necessarily „Double Dutch“ constructions as defined by the late Thijs Maarleveld, it seems that we are dealing with a much more broader phenomenon in naval construction than anticipated.

The approximate location of the final resting place of the aforementioned VOC-fluyt AMSTELLAND is actually known. The ship was probably heading to “Königshafen” (literally: king’s haven), an anchorage near List, to weather a storm, but the ship ran aground on 11th September 1751 at the north-westerly promontory of Sylt. This promontory became known as “Ostindienfahrerhuk” (literally: East Indiaman Point), a toponym still used today. According to a local chronicler, the wreck was situated in the surf-zone and its massive frames were still visible in his time, a hundred years later.

The Dutch maritime legacy in North Frisia

While the aforementioned wrecks reflect the high frequency with which Dutch ships either bypassed the North Frisian Islands or called at regional ports like Tönning or Husum, the local Frisian population was very familiar with the Dutch. North Frisians were active in regional coastal shipping and owned small single-masted vessels like bojers and smacks, used in coastal trade and fishering, which were frequently bought in the Netherlands. This is well reflected by the Uelvesbüll and Hedwigenkoog wrecks, which have been also built in the Dutch shell-first technique and which feature the characteristic leeboards and hull shapes of Dutch Wadden Sea vessels. Both wrecks were discovered in a scour behind a broken dyke. North Frisia was known in the Netherlands as “the little East”, as it was a recruiting area for seafarers hired for Dutch whaling vessels, VOC and WIC ships, and Baltic Sea traders. Many North Frisians spoke fluently Dutch and were given Hollandized names, which can be even found on their gravestones, most notably a mariner’s cemetery on the island of Amrum. Even the home decor was similar, with imported Delft ware tiles and some commissioned work of Friese schepentableaus At this time, the Dutch played a key role in the Baltic Sea trade network, which they inherited from the declining Hanseatic League. In this context one can also regard the foundation of the town of Friedrichstadt in 1621 (Frederikstad aan de Eider), a Dutch colony of remonstrant refugees, who were invited and granted the right to settle at the Eider River by Duke Friedrich III of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp. The invitation was not purely for altruistic reasons, as the duke hoped to revive the ancient trade route across the Schleswig isthmus by relying on the mercantile contacts of his new Dutch citizens.

Literature

A slightly altered version of this manuscript was published in Dutch translation – kindly provided by Robert de Hoop – in the newsletter of the Dutch Cultural Heritage Protection Agency:

Zwick 2021: D. Zwick, Scheepswrakken in de Duitse Waddenzee. De jongste dubbele planken. In: Tijdschrift van de Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed 4, 2021, 32-33.