Unterwasserprospektion von zwei Schiffwracks aus dem 19. Jahrhundert

Eine deutsche Übersetzung diesen Textes wird in Kürze folgen!

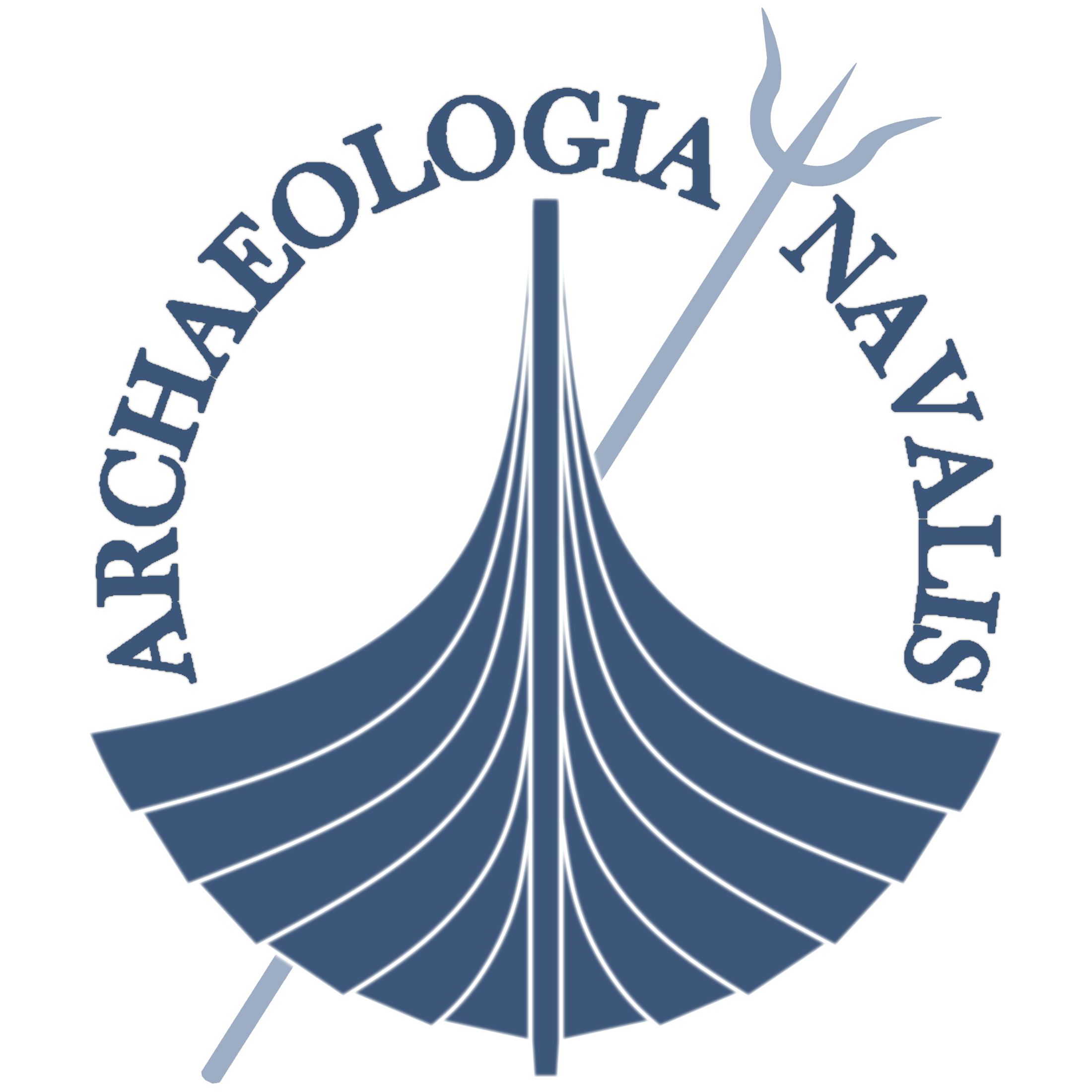

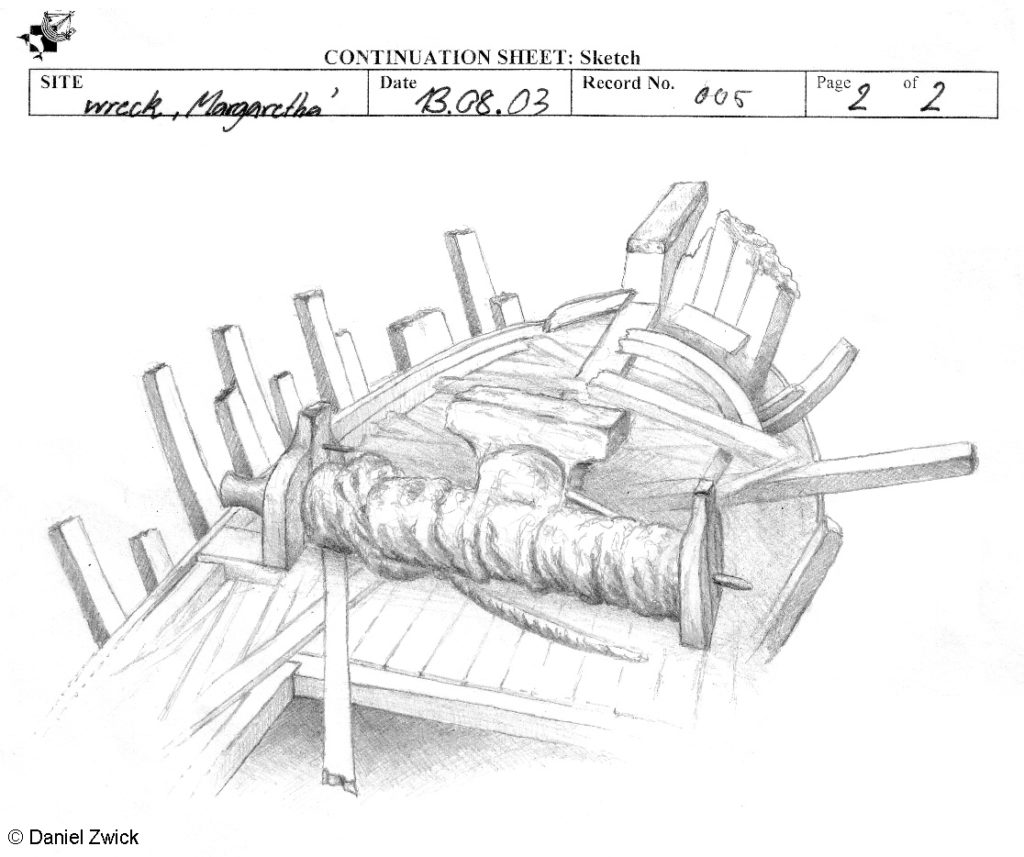

In 2003 I was involved in the ‘Krogen Project’ as archaeology student at Southampton University. Jon Adams conducted the underwater surveys with undergraduate and postgraduate students on two shipwrecks in the Stockholm Archipelago near Nynäshamn. Our first target was the wreck of the SEVERN, a British brig sunk in 1834. Our next target was the wreck of the Swedish brig MARGARETA, sunk in 1898. These were ideal training sites for us archaeology students, as the wrecks were extremely well preserved due to their sheltered locations and the low salinity in this part of the Baltic Sea, which explains the absence of the naval shipworm teredo navalis. Owing to these favourable circumstances, the wrecks are like time-capsules, as they are structurally in a similar state as wrecks that have sunk only a couple of years ago: The anchor cable is still coiled up around the windlass, the deck planks are mostly still in place and masts and yards are lying around the wreckage. The sight of the entire wrecksite must be stunning, but – as good as the preservational state is – the bad visibility only allows a small aperture impression. I sketched the bow section of the MARGARETA under water by always changing my position and combining the mosaics of the sketches, which came pretty close to the finding.

This view could be only achieved if a cofferdam is build around the wreck and the murky green water pumped out, so there’s much to be said for underwater sketching. The site was also a challenge, due to the coldness and bad visibility. When half a dozen of students (many of whom inexperienced divers – me included) were diving at the wreck, it was no wonder that great quantities of sediment were whirled up, until the visibility was nil.

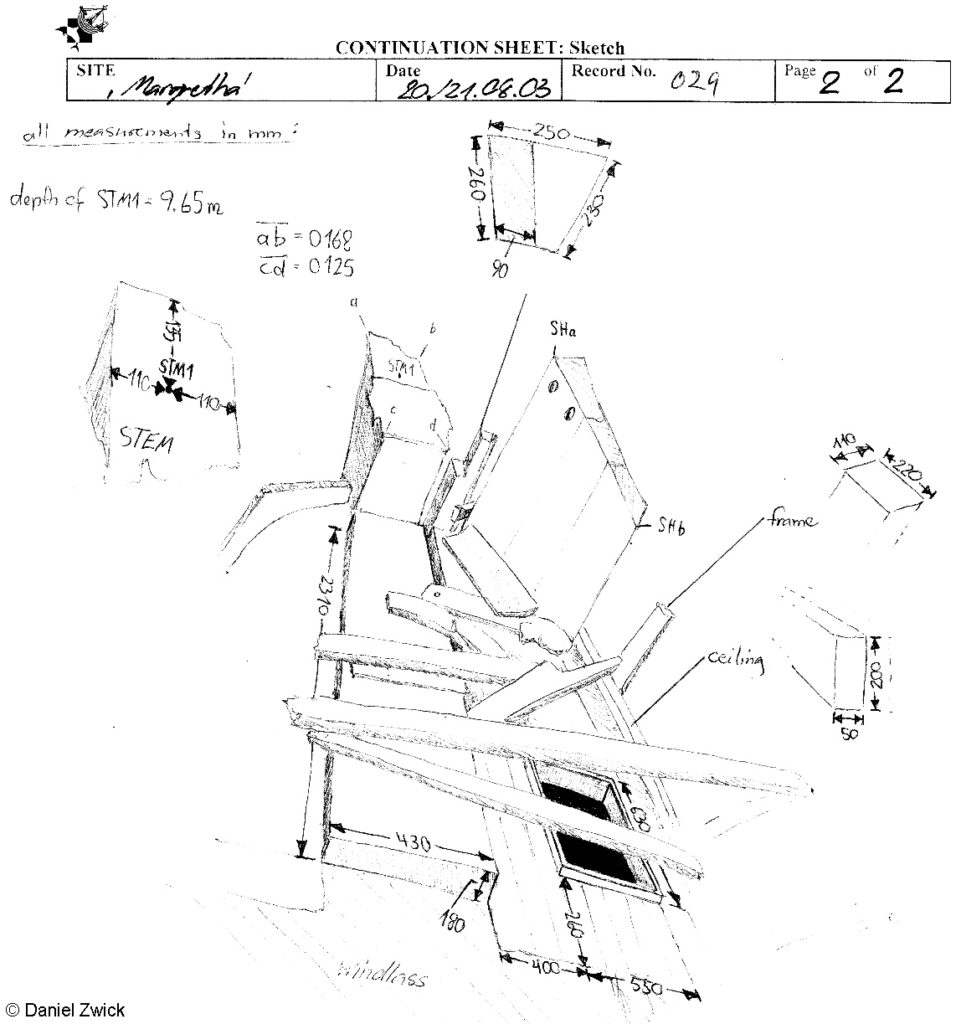

The direct survey method (DSM) is based on trilateration, in which many fixed points are measured in relation to each other – archaically with tape measure – and the outcome becomes gradually more accurate by the total number of measurements. The visibility was often so bad, that dive partners couldn’t see each other, so we communicated with each other by jerking the tape to signalise whether the partner should change his/her location. After all the points were measured, the data was fed into the DSM programme, which connected all the dots and rooted out all errors by deviation, presenting us with a neat 3D model of the wreck’s outlines. My underwater sketches contribute to a study on wreck site formation. For instance, in 1992 MARGARETA’s jib-boom was still in place, but in 2003 it has broken away. We also documented some parts of the rigging, like a top-mast with cross-trees and yard by taking photos (Ian) and drawings (me).

Aside from the surveys, we also made some excursions: Johan Rönnby (Södertörns University) showed us the temporary homes of Iron Age seal hunters on the island of Öja, the effect of the post-glacial rebound in relation to the topography and waterline, and we visited Bronze Age rock carvings in Norrköping, many of which depicted boats of the Hjortspring type. A highlight was a visit of the VASA (1628), where we were welcomed by Fred Hocker and Carl Olof Cederlund. 6 years later I returned to this magnificent wreck to carry out a survey on the VASA’s orlop-deck.

Conclusively it can be said, that this was one of the best projects I have ever been on: Smooth organisation, great team and a very steep learning curve.